Dealing With Difficult Landlords

Have you ever dealt with a bad landlord? Have you ever been in a bad lease that you desperately wanted to get out of? If you have, you know how it feels. If you haven’t, just imagine the pain of not being able to enjoy a hot shower after a long day’s work. If you’re a business owner, for example, imagine losing clientele during the day due to your landlord’s construction.

This article will cover the rights that residential and commercial tenants have when their landlord fails to provide basic requirements. General remedies provided to tenants throughout the U.S. will be explained. It’s important to remember that each state has its own rules as well.

Lease Types

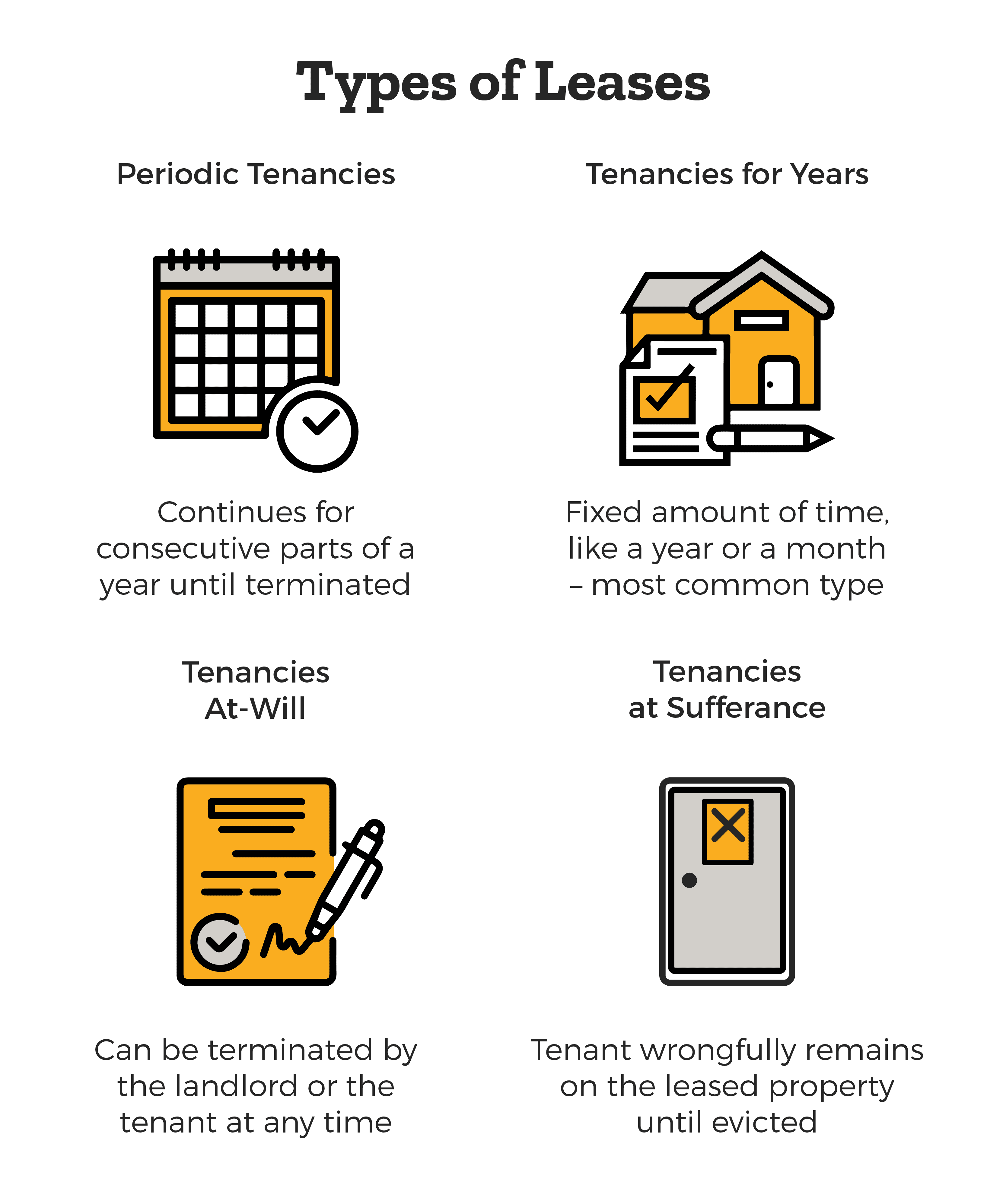

Before getting into the different things a tenant can do when dealing with a bad landlord, a quick review of the types of leases will be helpful. There are four basic types of leases: (1) periodic tenancies, (2) tenancies for years, (3) tenancies at will, and (4) tenancies at sufferance.

A periodic tenancy is a type of lease that continues from year to year or for consecutive parts of a year (e.g., weekly or monthly) until terminated by proper notice by either the landlord or tenant. A tenancy for years is a type of lease that begins and ends at agreed-upon dates. In other words, it’s a lease for a fixed amount of time, like a year or a month. Most people have a tenancy for years. No notice is needed to end the lease because the landlord and tenant already know when the lease will end.

A tenancy at will is a type of rental agreement that can be terminated by either the landlord or tenant at any time. A tenancy at sufferance occurs when a tenant wrongfully remains on the leased property after the lease ends, which lasts only until the landlord takes steps to evict the tenant.

Leases are also divided into residential and commercial leases. A residential lease is a lease for living purposes. A commercial lease involves the lease of a rental unit for business purposes rather than living purposes. Both types of leases have protections for tenants. However, there is a remedy available to residential tenants that commercial tenants do not get. This remedy is the implied warranty of habitability and will be discussed later in this article.

Scenarios of Landlord Abuse

Before explaining the legal principles that provide protections to tenants, two specific scenarios of landlord abuse will be provided as examples to understand how tenant rights and remedies function. One scenario for residential tenants and one scenario for commercial tenants will be shown.

In the residential scenario, the landlord fails to provide electricity or hot water for a long period of time. In this scenario, imagine not having running hot water or electricity for a few days. Situations like this are simply unfair. When signing a lease with a landlord, most lease agreements require the landlord to provide things such as running water and electricity. Two remedies are available to tenants in this sort of situation, which will be discussed shortly.

In the commercial lease scenario, the landlord begins construction on real estate leased by a commercial tenant. The construction then results in decreased profits for the tenant’s business since the construction prevents customers from entering the business.

Protections and Remedies for Tenants

Now that the scenarios have been provided, the rules that protect tenants will be reviewed and then applied to the scenarios. Landlords have several duties toward tenants that must be performed according to the law. An explanation of some of these duties will better illustrate the remedies available to tenants when landlords fail to perform.

Quiet Enjoyment

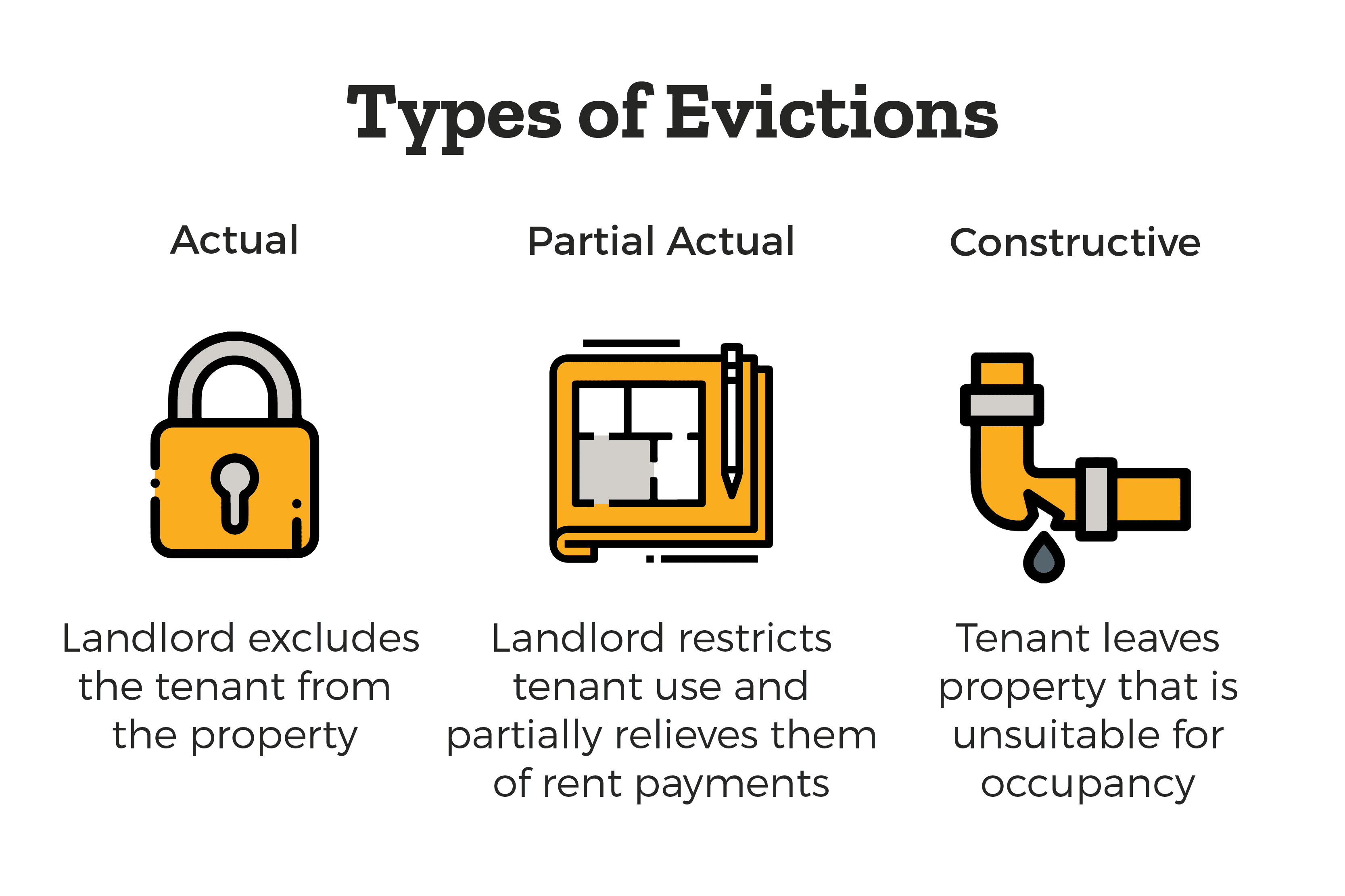

There is implied in every lease a promise, also called a covenant, that the landlord will not interfere with the tenant’s quiet enjoyment and use of the premises. This promise, or covenant of quiet enjoyment, may be breached in three ways: actual eviction, partial actual eviction, or constructive eviction.

Actual Eviction

Actual eviction occurs when the landlord or a previous tenant of the landlord excludes the tenant from the entire rental property. Payment of rent by the tenant is not required if there has been an actual eviction.

Partial Actual Eviction

Partial actual eviction happens when the tenant is physically excluded from only part of the rental property. The landlord can relieve the tenant from any more payments of rent even though the tenant continues to use a part of the rental property. Partial actual eviction by a third person, such as the landlord’s previous tenant, allows the current tenant to decrease the rent. The tenant’s remedies for this occurrence will differ depending on whether the partial eviction was caused by the landlord or a landlord’s tenant.

Constructive Eviction

Constructive eviction occurs when a landlord’s failure to provide certain requirements makes the rental property “unsuitable for occupancy,” or, in other words, difficult to live in. To establish a claim for constructive eviction, the tenant must prove the following:

- The landlord, or persons acting for him, breached a duty to the tenant (acts of neighbors or strangers will not be enough);

- The breach substantially and materially deprived the tenant of use and enjoyment of the premises (e.g., flooding, absence of heat in winter, loss of elevator service in a warehouse);

- The tenant gave the landlord notice and reasonable time to make repairs; and

- After such reasonable time, the tenant moved out of the premises.

A tenant who has been constructively evicted may terminate the lease agreement (i.e., is relieved from paying rent) and may also sue for damages. Constructive eviction is often raised as a defense in a landlord’s suit for damages or rent.

In the residential lease scenario, the landlord’s failure to provide hot water or electricity is a breach of the landlord’s duty to the tenant. This duty, however, must be mentioned and agreed to in the lease. Make sure that your lease agreement requires your landlord to provide hot water and electricity. Seek legal advice if you’re unsure.

If the lease includes this requirement, then the tenant must provide the landlord notice of the fact that there is no hot water or electricity. The notice requirement is important since a landlord cannot make a repair if he or she does not know of any repairs needed. If a reasonable time has passed since making the request, the tenant may vacate the premises and stop making rent payments to the landlord. What is reasonable depends on the facts of each tenant. The tenant can also sue for any damages that resulted from not having hot water and/or electricity.

The principles of constructive eviction can also be applied to the commercial lease scenario mentioned above. In that scenario, the landlord’s construction causes the tenant’s business to decrease because the construction prevents foot traffic to the tenant’s business. In that case, the landlord must have agreed in the lease agreement that he or she will not interfere with the tenant’s business. If the lease does not specifically state that the landlord cannot interrupt foot traffic to a tenant’s business, then the remedy of constructive eviction is not available. This again shows the importance of specifically setting out the details of a lease agreement. Talk to a lawyer about your legal rights before entering into a lease.

If your written lease does not specifically require your landlord to provide things such as hot water or electricity, there is an added layer of protection provided only to residential tenants: the implied warranty of habitability. Commercial tenants cannot use this remedy. The implied warranty of habitability will be discussed next.

Implied Warranty of Habitability

More than half of the states in the U.S. have the implied warranty of habitability for residential landlords. The warranty requires landlords to keep their residential properties fit and habitable for human habitation throughout the duration of the landlord-tenant relationship. Further, this warranty is implied by the law, which means that a residential tenant has this warranty whether or not the warranty is specifically required in the rental agreement. This is different than the remedy of constructive eviction since that remedy requires the rental agreement to specifically set out the landlord’s duties, such as warranties for habitability, hot water, and electricity.

Furthermore, the implied warranty of habitability is inapplicable to commercial tenants, unlike constructive eviction. Because of this, the commercial tenant in the factual scenario above would not have the legal right to use this remedy.

Standard

“Reasonably Suitable for Human Residence”

The standard usually applied to determine whether a landlord violated the implied warranty of habitability is the local fair housing code (if one exists). Most fair housing codes require the landlord to provide hot water and electricity. If there is no fair housing code under the laws of your state, then ask whether the conditions are “reasonably suitable for human residence.”

In the residential fact scenario above, the implied warranty of habitability would protect the tenant. This is because the landlord’s failure to provide hot water or electricity is a violation of the typical fair housing code and, therefore, a violation of the implied warranty of habitability. Even if the laws of your state do not include a fair housing code, or if the fair housing code does not specifically require landlords to provide hot water or electricity to residential tenants, then the implied warranty will still provide protection. This is because the standard of “reasonably suitable for human residence” still applies, which means that the landlord’s failure to provide hot water or electricity creates conditions on the property that are not reasonably suitable for human residence.

Remedies

Once a violation of the implied warranty has been established, a residential tenant has the following remedies:

- Tenant may move out and terminate the lease (as in a constructive eviction).

- Tenant may make repairs directly and offset the cost against future rent payments.

- Tenant may reduce rent to an amount equal to the fair rental value in view of the defects in the property.

- Tenant may remain on the leased real estate, pay full rent, and sue for damages against the landlord.

The tenant in the residential lease scenario would be able to pick one of the remedies listed above. For example, the tenant can (1) move out and end the lease, (2) pay for a repairman to fix the electricity or lack of hot water and subtract that amount from the monthly rent, (3) lower the monthly rent to an amount that the same rental unit would be without hot water and/or electricity, or (4) stay on the land, continue to pay rent, and sue the landlord for failing to provide hot water or electricity. Option 3 probably wouldn’t be wise since it would still leave the tenant without hot water and/or electricity.

Finding Your Solution

Tenants under U.S. law are provided many protections against landlords who abuse lease agreements. In some states, such as California or New York, tenants are provided even more protections than the ones mentioned in this article. That’s why it’s helpful to seek legal advice before entering into a lease agreement. Choosing the right remedy depends on the facts of each case.

Sources

- Singer, Joseph William. Property. Wolters Kluwer, 2017. “California Landlord-Tenant Practice.” CEB, ceb.com/california-landlord-tenant-practice.

- Williston, Samuel. A Treatise on the Law of Contracts. Thomson, West, 2004.

- Powell, Richard R., and Michael Allan. Wolf. Powell on Real Property: Michael Allan Wolf Desk Edition. LexisNexis Matthew Bender, 2009.