Protecting an Estate

When a person passes away, they often leave behind real estate and personal property. This is generally referred to as a decedent’s estate. An instrument that functions to legally declare a plan to distribute the decedent’s estate is called a will. A person who dies in Florida with a valid will is said to have died testate. Thus, such a person is called a testator. Conversely, a person who dies without a will is said to die intestate. There is no legal requirement in Florida statutes that a person must have a will. This is because, in part, Florida has a set of intestacy laws that are used to dispose of the decedent’s property if someone passes away without a will. However, if the decedent would like to have his or her property disposed of in a specific way, he or she will need a will. This is what is known as testamentary intent.

Florida recognizes several types of wills, including wills that were not created in Florida or even in the United States. Florida will consider an out-of-state or foreign will to be valid if it was created legally and in accord with the laws of will formation in the place from which it came. Florida does not recognize wills that were written in the testator’s handwriting and signed by the testator or holographic wills. This is because Florida requires that all valid wills be formed in accord with several formalities to ensure that the testator had a present intent to form a valid last will and testament. This is known as attestation.

The procedure of attestation has many requirements that may be complex. A preprinted template will form may or may not achieve all of the testator’s wishes. This is a major reason why many people hire attorneys who specialize in estate planning to ensure the will formation process is done correctly. A testator may hire an attorney of their choosing, but the state will not provide one to the testator at no cost.

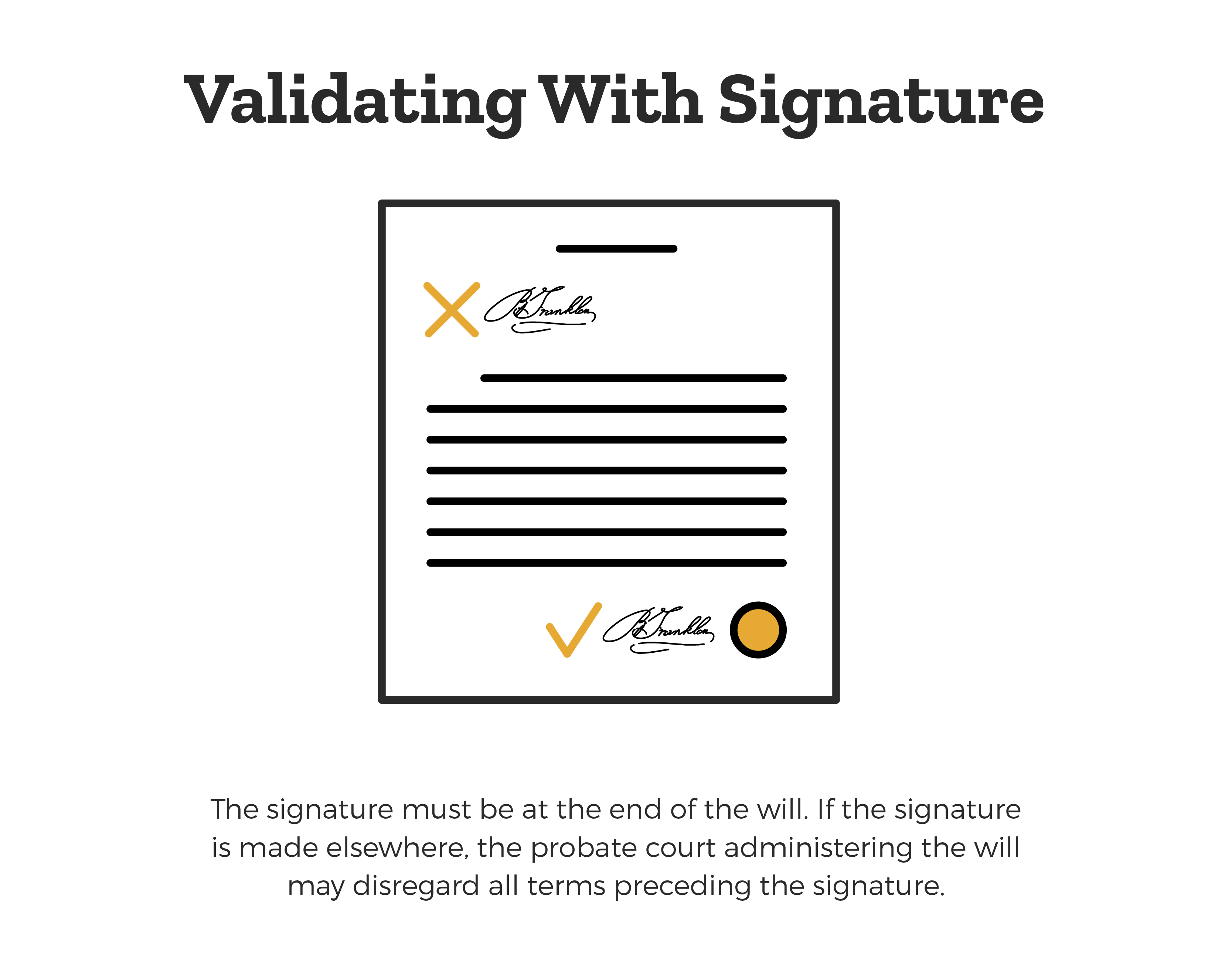

To form a valid Florida will, the testator must be at least 18 years of age and of sound mind at the time the will is executed. The will must be in writing, and the testator must sign the will. Florida requires that the testator sign at the end of the will. If the signature is not at the end of the will, the probate court administering the will may disregard all terms preceding the signature. The testator does not have to sign his or her complete legal name. The signature need only show that the testator intended to sign (e.g., marking an X on the signature line is acceptable). If the testator is not capable of signing, another person may sign the will. However, the other person must sign the testator’s name on the will at the testator’s direction in the presence of the testator. Finally, the will must be signed by at least two attesting witnesses who are each independently capable of understanding the nature of creating a will and have the intent to bear witness to the creation of the will. The witnesses must also sign the will in each other’s presence. The witnesses need not actually see the testator sign the will. At a minimum, the testator need only acknowledge to the witnesses that he or she has signed the will. There is no age requirement for witnesses on a will.

Witnesses may also be intended beneficiaries who are included in the will. These witnesses are known as interested witnesses. However, the lawyer(s) who drafted the will may not receive a gift from the will unless the lawyer is related by blood to the testator. To certify that these requirements have been followed and to simplify the process, the testator may execute a self-proving affidavit. The self-proving affidavit will allow the will to be administered without further proof of attestation, but the affidavit must be formed in the presence of an officer authorized to administer oaths, such as a notary public.

If the testator wishes to change or modify the terms of the will, Florida recognizes several different ways by which this may be legally accomplished. The testator may expressly modify the will by executing an additional document that must identify the specific will it is intended to modify. This type of document is called a codicil, and it must be formed with the same formalities used to create a will. However, if the testator wishes to terminate an existing will, he or she may do so in a subsequent writing that is not a codicil or a new will. The revoking document need only identify the will to be revoked.

The testator may execute a new will to supersede the older will. However, the new will must contain language that indicates the testator’s intent for the old will to be revoked and the new will to control. Most will forms contain a clause to this effect. The testator may also revoke a will by physically destroying the will document (e.g., tearing, burning, shredding) with a present intent to revoke. Merely destroying the document unintentionally would not have the legal effect of revoking the will. However, such an act will revoke the entire will. Florida law does not allow for partial revocation by destroying a will. The destroyed will may be revived by executing a new testamentary document in accord with attestation formalities, such as a new codicil. A revived will has the same effect as the will before it was destroyed.

A will that has been proven or self-proven to be attested will then undergo a process based on state laws, called probate. Any property that is included in a valid will or by intestacy is considered probate property. All of the decedent’s remaining property may pass by some other means such as joint property ownership, for example. In Florida, the process of probate is conducted and supervised by the circuit courts. The process of probate includes proving transfers of title, payment of the decedent’s debts, and distribution of property. A person or group of people must be appointed to manage the decedent’s estate during probate, known as the personal representative(s).

To qualify as a personal representative in Florida, the person must have legal capacity (be of sound mind and able to make decisions), be at least 18 years of age, be a Florida resident (if not related by blood to the decedent), and never have been convicted of a felony. The personal representative may be appointed by language in the will or by the court if the will is silent as to who shall be appointed. All personal representatives in Florida owe a fiduciary duty to the decedent’s estate. This means that personal representatives are required to maintain a high standard of care and loyalty to the estate.

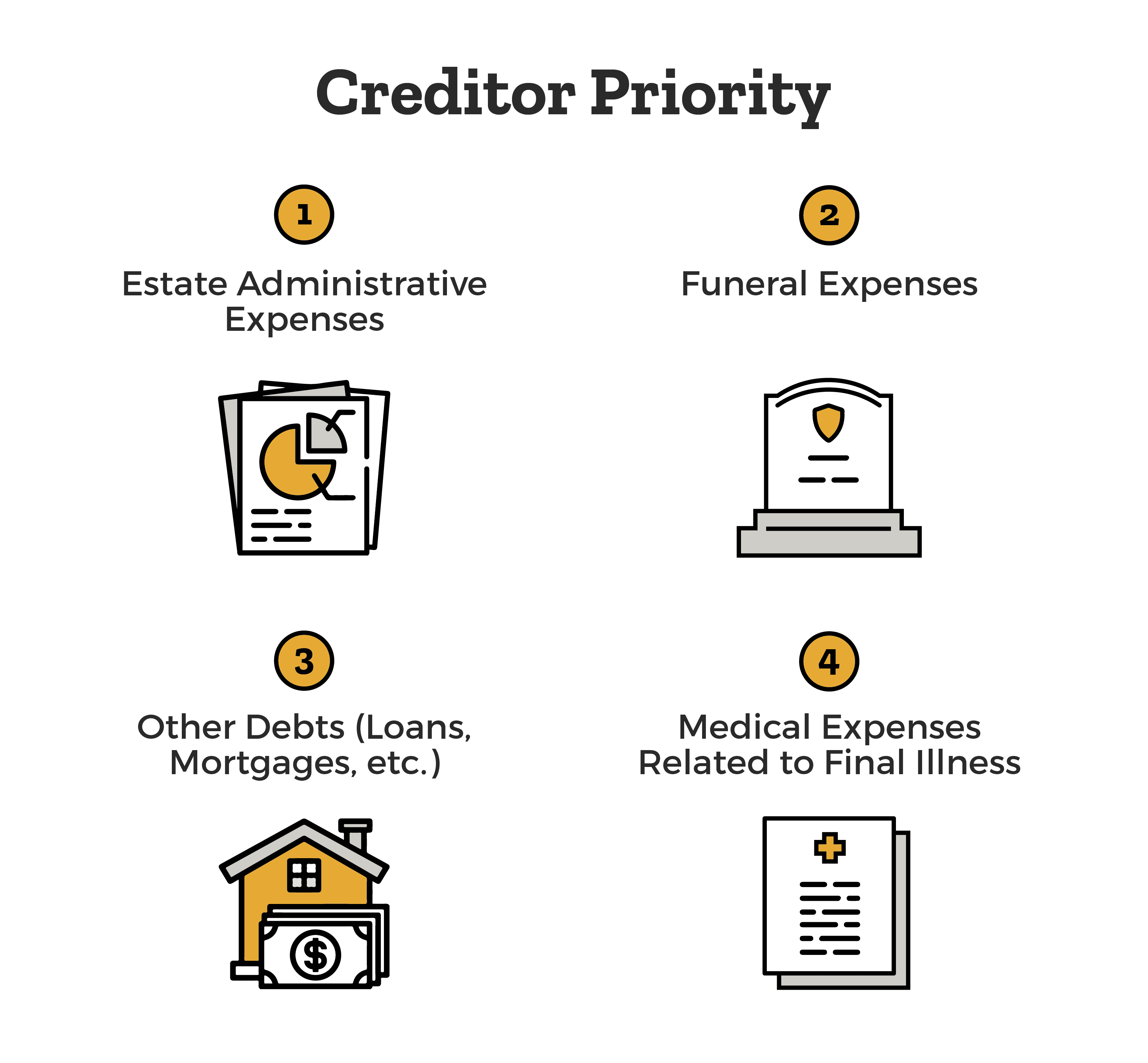

A personal representative who fails to perform their duties may also be removed from this position. A personal representative is entitled to reasonable compensation to be paid from the decedent’s estate for performing their duties associated with the decedent’s estate. The decedent’s creditors are to be satisfied in the following order: expenses related to the administration of the estate, funeral expenses, the decedent’s debts that are prioritized by federal law, and medical expenses associated with the final illness of the decedent. For estates worth $75,000 or less, Florida applies a simplified and expedited version of probate called summary administration. All estates worth more than $75,000 will be subject to a stricter and more time-consuming process called ancillary administration.

As previously noted, the property of decedents who pass away in Florida without a will is not subject to probate code, and it is to be distributed according to the laws of intestacy or intestate succession. Florida utilizes a per stirpes scheme of property distribution based on the existence of the decedent’s surviving family members. Accordingly, if only a spouse survives the decedent, the spouse will take all of the decedent’s estate. If children and no spouse survive the decedent, the children (minor children or adults) will take all of the estate in equal shares. If the decedent dies with no relatives or heirs, the estate will escheat (pass to) Florida.

Notably, the spouse making a claim to a decedent’s estate must have been married to the decedent at the time the decedent passed away. For example, a clause in a decedent’s will that states, “all my property to my wife …” will not be effective if the testator divorces before the administration of the will. Thus, the former wife cannot inherit a share of the estate unless she was specifically named in the will. If a spouse marries the testator after a will is formed, such spouses are known as pretermitted spouses, and they may inherit the applicable intestate share of the estate.

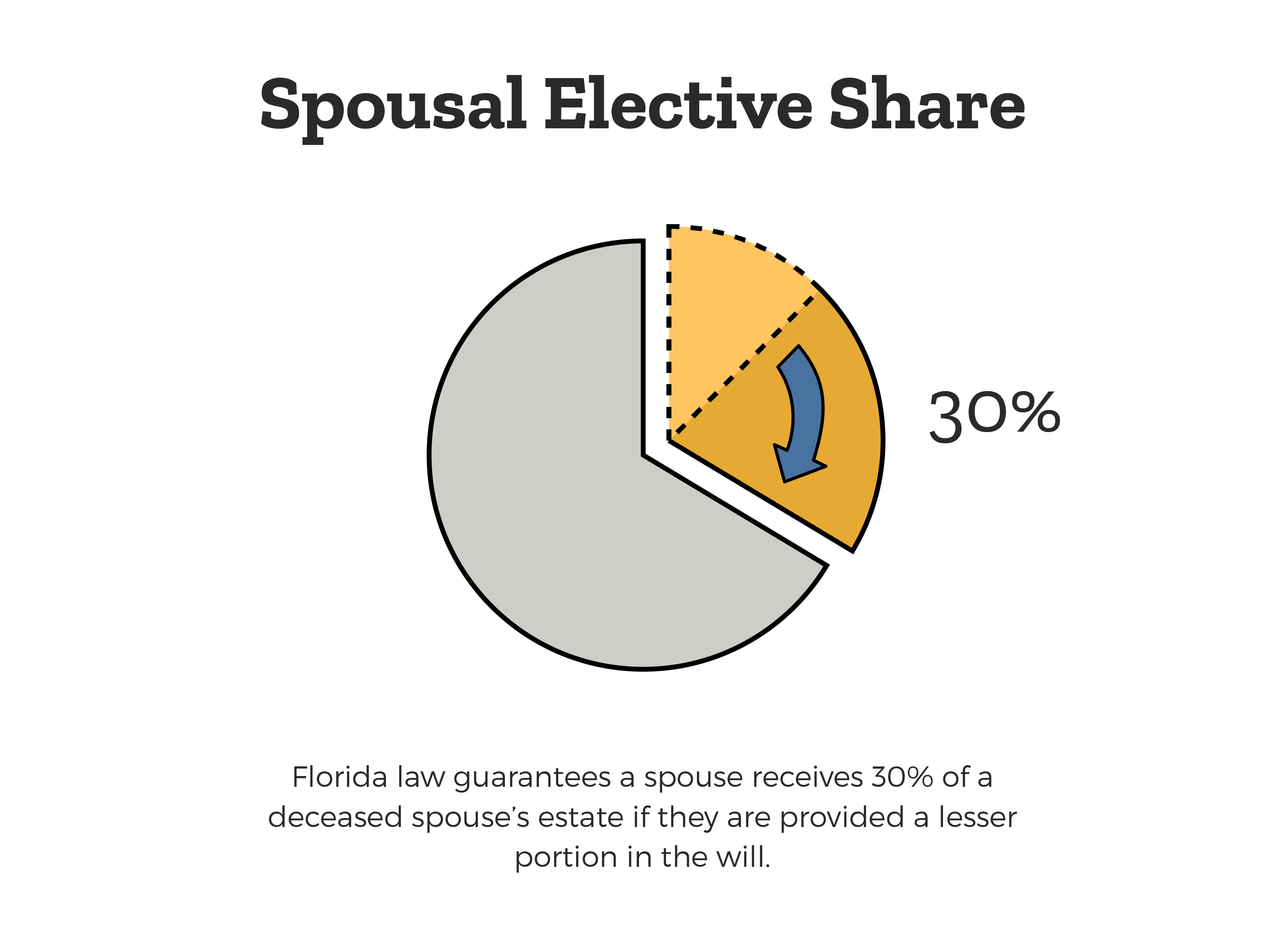

A spouse may choose to inherit their elective share, which is guaranteed by Florida law to be 30% of the deceased spouse’s estate, if the decedent’s will provides a lesser devise to the spouse. If a spouse or any other party wishes to contest the administration of a will, they must have an interest in the will they are seeking to challenge. Most often, will challenges are based on the capacity (or lack thereof) of the testator. Wills may be voided if the court determines that the will was formed subject to duress, fraud, or undue influence.