Who Is at Fault?

Florida law imposes obligations relating to public safety on individuals and organizations. Whenever a natural person or group falls below or deviates from these expectations, the law attempts to protect those who have been harmed. This type of harm is legally referred to as a tort. One of the most common torts occurs when one party is required to act or maintain a certain standard of reasonable care to minimize the risk of danger to the public, and the same party does not fulfill the duty of care (the defendant). As a result, someone else (the plaintiff) is harmed or damaged by it. This harm could have been suffered by as few as one person or as many as thousands of people. The law often tries to restore the losses of the party who suffered the harm by ordering they be paid for their losses. These financial awards are known as damages.

Frequently, people hire personal injury attorneys and law firms to help guide them and ensure the process is completed thoroughly and fairly. Both parties may hire an attorney of their choice. However, Florida does not provide attorney representation to either party at no cost in these situations. Florida will allow for an attorney to represent a person who has been harmed at no cost, though, unless and until the attorney recovers money for them. In which case, the attorney may keep a predetermined percentage of the recovery. This is what is called a contingency agreement or contingency-based representation.

However, there are strict rules that attorneys must follow when making contingency agreements with their clients. For example, the agreement must be in writing and signed by the client. It must also state how the attorney’s fees are to be calculated, what other expenses are to be deducted, when they are to be deducted, and the fees must be reasonable. These agreements may not be made in criminal cases. If the attorney does not carry out the representation fully, he or she may be paid for the work performed on the case at the time the representation ended. Attorneys may also provide a free consultation to review the facts of the case.

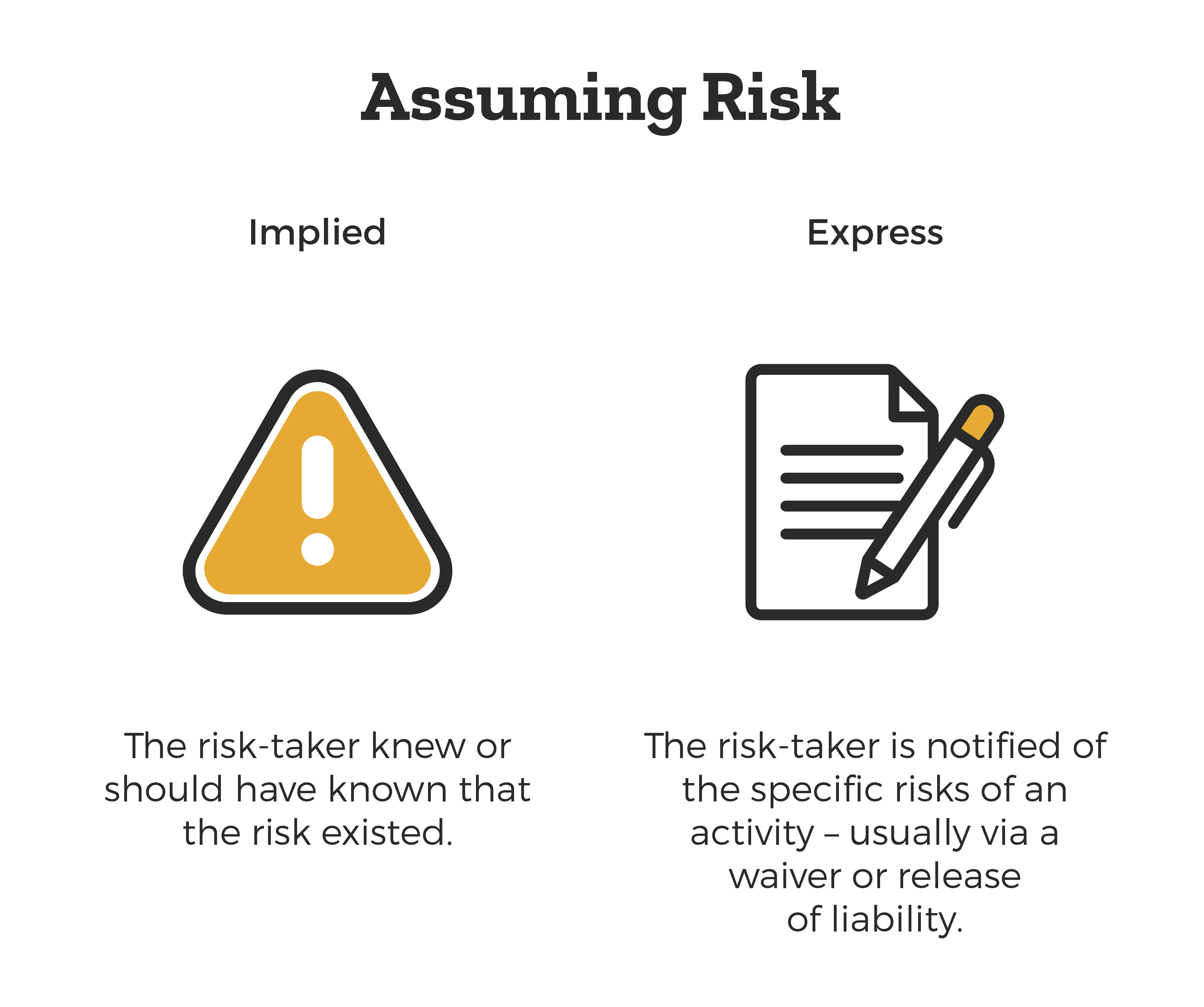

Attorneys may also be hired to defend those who have been accused of negligence. Florida law recognizes some major defenses to negligence claims. The strongest legal defense to a negligence claim is known as assumption of risk. This defense basically says the plaintiff was aware of and capable of understanding the risks involved with the particular activity before participating in the act or acts that harmed them. There are two main types of assumption of risk: implied and express. Implied assumption is when the person who took the risk knew or should have known that the risk existed without being told that the risk existed.

This assumption would be quite strong in a situation such as bungee jumping when many of the risks to personal safety are quite obvious. However, Florida law does not recognize this assumption as a valid defense to negligence accusations. Florida law requires that the plaintiff be expressly informed (orally or in writing) of the specific risks involved with the particular activity performed. This notification is often given in writing, which is called a waiver or release of liability, and it is required to be signed by the party assuming the risk. Notably, there are limits to these waivers. Most often, Florida courts will disregard a release of civil liability in cases involving intentional acts to harm others on the part of the defendant.

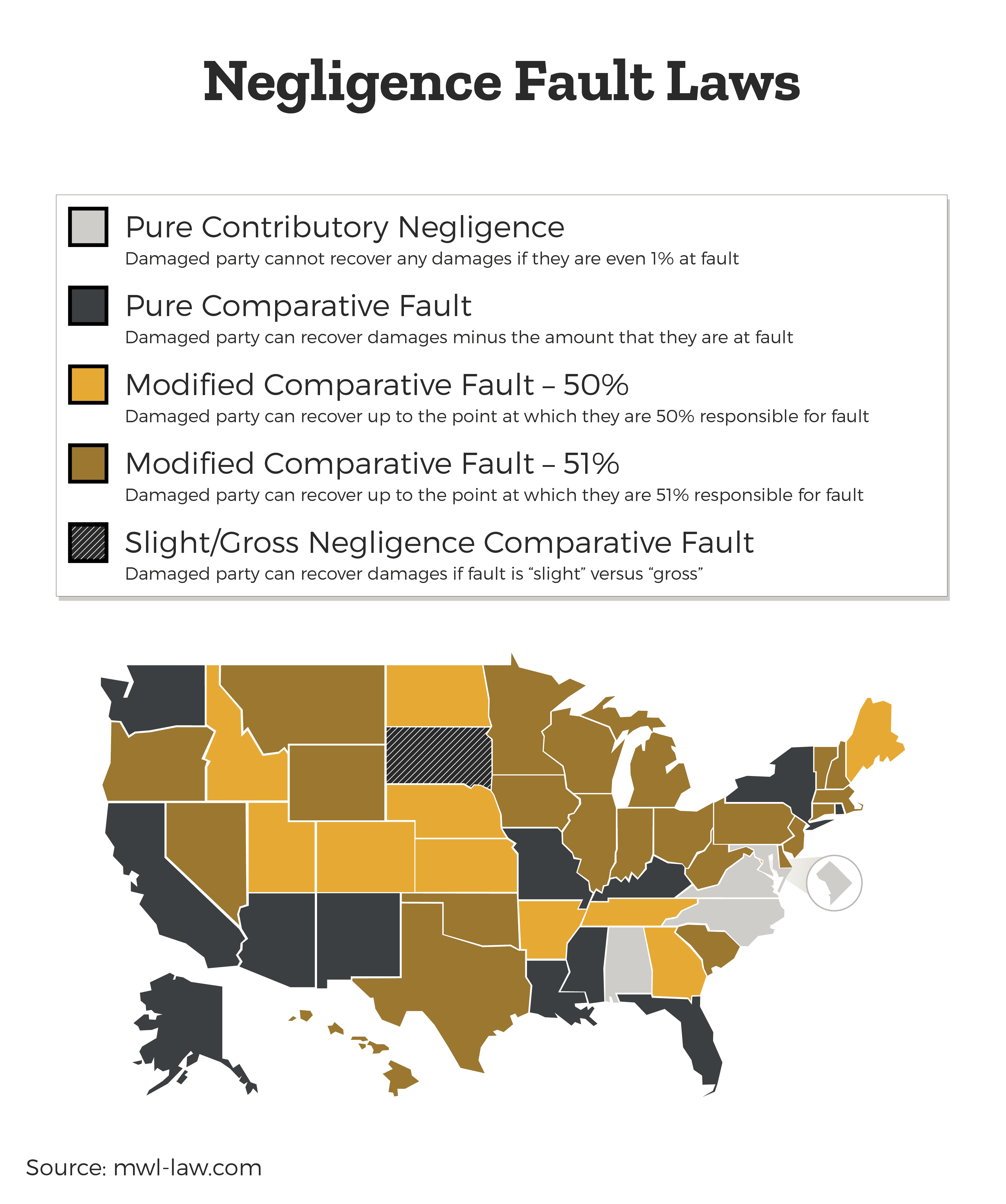

In Florida, the defendant may also demonstrate how the plaintiff contributed to his or her own injury. Accordingly, the defendant may seek to have the plaintiff’s recovery reduced or completely denied. This policy is referred to as comparative fault or comparative negligence. Florida is a pure comparative negligence state. This means that the plaintiff’s contribution to his or her own injury (determined by a jury) will be deducted from his or her final recovery. In cases involving negligence committed by a government agent, employee, or officer, Florida may not be sued unless the government permits to be sued. This defense is known as sovereign immunity. This defense is also limited to unintentional offenses. It does not apply to government acts that are routinely performed as a part of regular government operations and do not involve discretion or decision-making (e.g., maintaining highways and schools).

The defendant may also rely on the occurrence of later cause of injury, which makes it difficult or impossible to determine which event caused the injury. For example, the plaintiff is transported by ambulance for treatment of a head injury, and the plaintiff hits his or her head again inside the ambulance. This is what is known as an intervening cause because this can interfere with the plaintiff’s ability to prove the cause of his or her injury. An intervening cause that functions to bar recovery by the plaintiff completely is called a supervening cause.

Generally, the law does not impose a duty on individuals to rescue others from dangerous situations. So if one finds a person who is presently in danger, the law does not require anyone other than appropriate authorities (e.g., firefighters or police) to come to their aid. However, in Florida, the Good Samaritan Rule does protect rescuers from liability for damage caused during the rescue, unless the court finds that the rescuer also created an unreasonable risk of danger during the rescue.

A duty to ensure the safety of others may be expressly imposed in the language of a Florida statute. For example, if a law reads, “all escalators must be inspected every six months,” the duty is owed to those who use escalators and suffered injuries while using the escalators. If the owner of an escalator that is used by the public does not comply, he or she may be liable for negligence per se. However, Florida law does not automatically hold the defendant liable for negligence per se. Negligence per se may be considered by a jury when making an ultimate decision as to whether the defendant committed ordinary negligence.

In negligence cases involving particularly dangerous situations, liability may be imposed even without proving ordinary negligence. This application of negligence is known as strict liability. The law mainly recognizes three categories of this situation: abnormally dangerous activities (e.g., detonating explosives), wild and dangerous animals, and defective products (defects in design, manufacturing, or failure to provide adequate warnings of hidden or non-obvious danger). In cases involving the use of another person’s land, the highest duty is owed to customers conducting business on the property or invitees. Less strict duties are also owed to people who simply have permission to use or be present on the premises. These people are called licensees. No duty is owed to trespassers. However, landowners may not intentionally harm trespassers, such as setting traps to injure, kill, or physically confine trespassers.

Employers may be held liable for the negligence of employees acting within the scope of their employment. For example, the employer of a delivery driver may be liable for a car accident that happened while the driver was making his or her deliveries. This theory of liability is known as respondeat superior, and it also does not provide recovery for intentional or reckless acts of employees. Doctors may be held liable for injuries to their patients sustained within the course of providing treatment (e.g., during surgery). This personal injury claim is called medical malpractice. However, in an attempt to balance the interests of physicians and patients, Florida law has placed several limitations on this type of recovery.

Plaintiffs are required to prove that the acts (or failure to act) of the defendant caused harm. Specifically, the plaintiff has to prove that this was more likely true than not true. This is the standard that the law refers to as preponderance of the evidence. Intentional or reckless acts tend to carry heavier penalties. So they must be proven to a higher standard known as clear and convincing evidence. A court or jury may find that multiple tortfeasors caused harm to the plaintiff. So Florida law gives the plaintiff the option to sue one defendant for the entire amount or to sue more than one defendant according to the percentage of fault assigned by a jury to the individual tortfeasor. To encourage the public to address causes of injury on their own, evidence of subsequent remedial measures or attempts to correct causes of injuries (e.g., repairing a cracked sidewalk after a plaintiff trips and falls) or offers to compromise (e.g., offering to pay the plaintiff’s medical expenses) is not to be admitted in court as evidence of the defendant’s liability.

Courts award damages to plaintiffs to restore them to the position they were in before the injury happened. These awards are known as actual damages. In personal injury cases, plaintiffs may recover for medical expenses, pain and suffering, lost wages, and a reduction in future earning capacity. However, it is important to mention that plaintiffs who have only suffered economic losses may not recover for negligence. According to the Economic Loss Rule, negligence requires some noneconomic loss such as personal injury or property injury. For example, if the defendant causes a business owner to lose customers without damaging the plaintiff’s person or property, the plaintiff must sue under a different cause other than negligence.

In Florida, the defendant may deduct any funds paid to the plaintiff from his or her personal health insurance company or other sources that were applied to the plaintiff’s recovery from the overall amount of damages awarded. The Eggshell Plaintiff Rule says plaintiffs who are particularly sensitive to an injury can recover damages resulting from their specific sensitivity, regardless of whether the defendant was aware of the sensitivity. For example, a pregnant woman whose injury is worsened due to her pregnancy may recover for all injuries even if the defendant was unaware of the pregnancy.