What Is A Will?

A will is a legal document that directs the disposition of a person’s estate, including their personal property and real estate, at their death.

- The person who makes a will is called a “testator” and has died “testate.”

- A person who has died without a valid will, however, is called a “decedent” and has died “intestate.”

- Bequests are directives within a will that instruct the transfer of the possessions to beneficiaries.

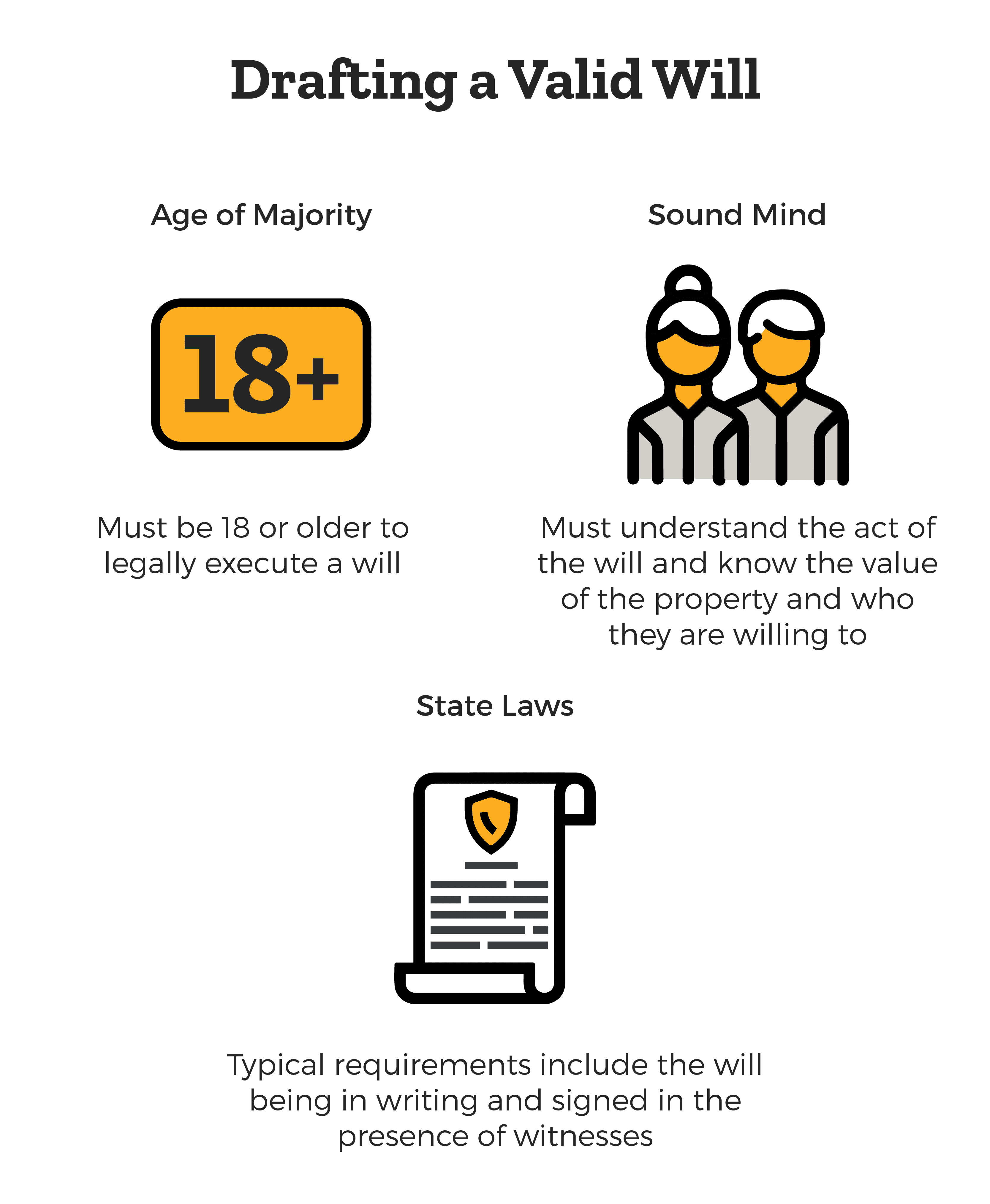

What Makes a Valid Will?

Firstly, a person must be at least 18 years of age (the age of majority) to execute a valid will legally.

The testator must also have a “sound mind” or capacity, showing that they:

- Understand the nature of the act of making a will

- Know the nature and approximate value of their property

- Know their family members or loved ones and understand whom they are leaving their property to

Additionally, the will must satisfy the laws of the state regarding the procedure. Although states vary in their requirements, most all agree that the will must be in writing and include the testator’s signature (signed in the presence of two witnesses), plus be signed by two additional competent witnesses (signed in the presence of the testator). Some states vary with the number of witnesses they require necessary.

Some state laws have additional requirements, such as requiring the testator’s signature at the end of the will and for the testator to “publish the will,” meaning the testator told the witnesses that the document was his or her last will and testament.

It is best to check with an attorney who specializes in estate planning to make sure of the specific legal requirements in your jurisdiction before drafting your will.

What Is an Executor?

A will also names an executor who is the person or persons responsible for carrying out the directions in the will. They first must pay all taxes or debts before making distributions to beneficiaries. An executor can be the attorney who helped prepare a will or any other person the deceased person trusted.

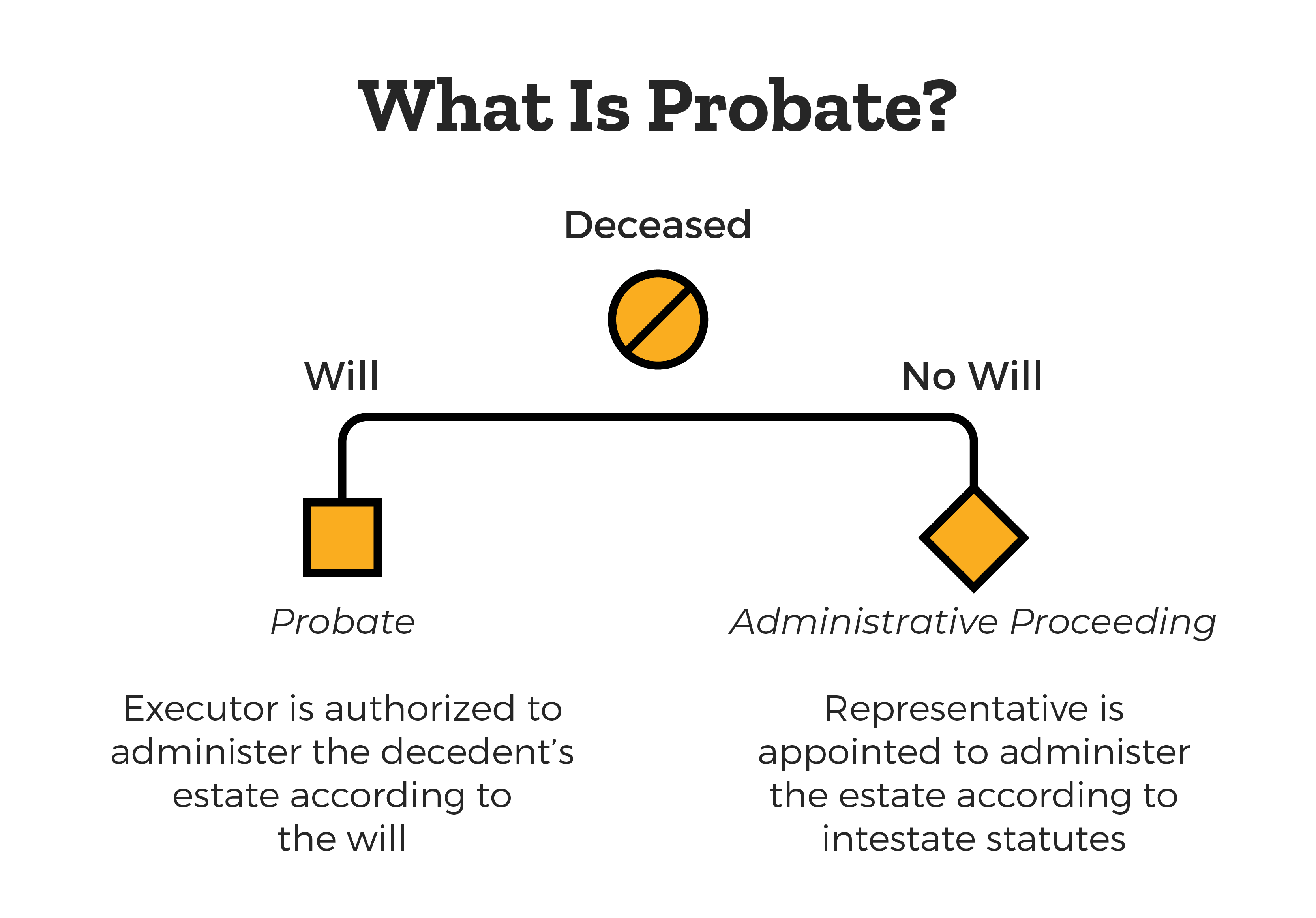

What is Probate?

Probate is the legal proceeding to administer the distribution of property when it has been determined a person has died with a valid will.

At probate court, the personal representative named in the will, the executor, is formally authorized by the court to administer the decedent’s estate.

If a person has died without a will or dies with a will that was improperly executed, then the surrogate court will not admit to probate, but there will be an administrative proceeding. During the administrative proceeding, a personal representative (administrator) will be appointed to administer the estate of the person according to the intestate succession statute.

How Does Intestate Succession Work?

Making a last will and testament is an essential part of estate planning. Without a valid will at the time of one’s death, all personal property, real estate property, and bank accounts will be subject to intestate succession, which is governed by the laws of the state one lived in at the time of his or her death.

Many people falsely believe if they die without a will that the state will receive their possessions.

The state will first attempt to distribute the estate under intestacy law.

What is intestacy law?

The intestacy law is arranged to try to distribute the decedent’s estate to people the legislature believes the decedent would have likely chosen if he or she did make a will.

Intestacy distribution starts with:

- The surviving spouse and children

- If not then to the decedent’s parents

- If not then to the decedent’s siblings and their issue

- If not then to the decedent’s grandparents and the grandparents’ issue (the decedent’s aunts, uncles, and cousins)

Intestate succession eventually cuts off relatives who are too far removed, so the state will only step in and take the estate if a person died without having any close living relatives.

In most jurisdictions, if the decedent has left a surviving spouse and children, the surviving spouse will take the first half or one-third of the estate. Some other states give a specific dollar amount, e.g., the first $50,000 to the surviving spouse, plus the one-third or half of the remaining balance. In cases where the amount of the estate is less than the spouse’s requisite amount, the spouse will simply take the entire estate.

In cases where a decedent has a surviving spouse but no other direct descendants, the surviving spouse will usually receive the entire estate.

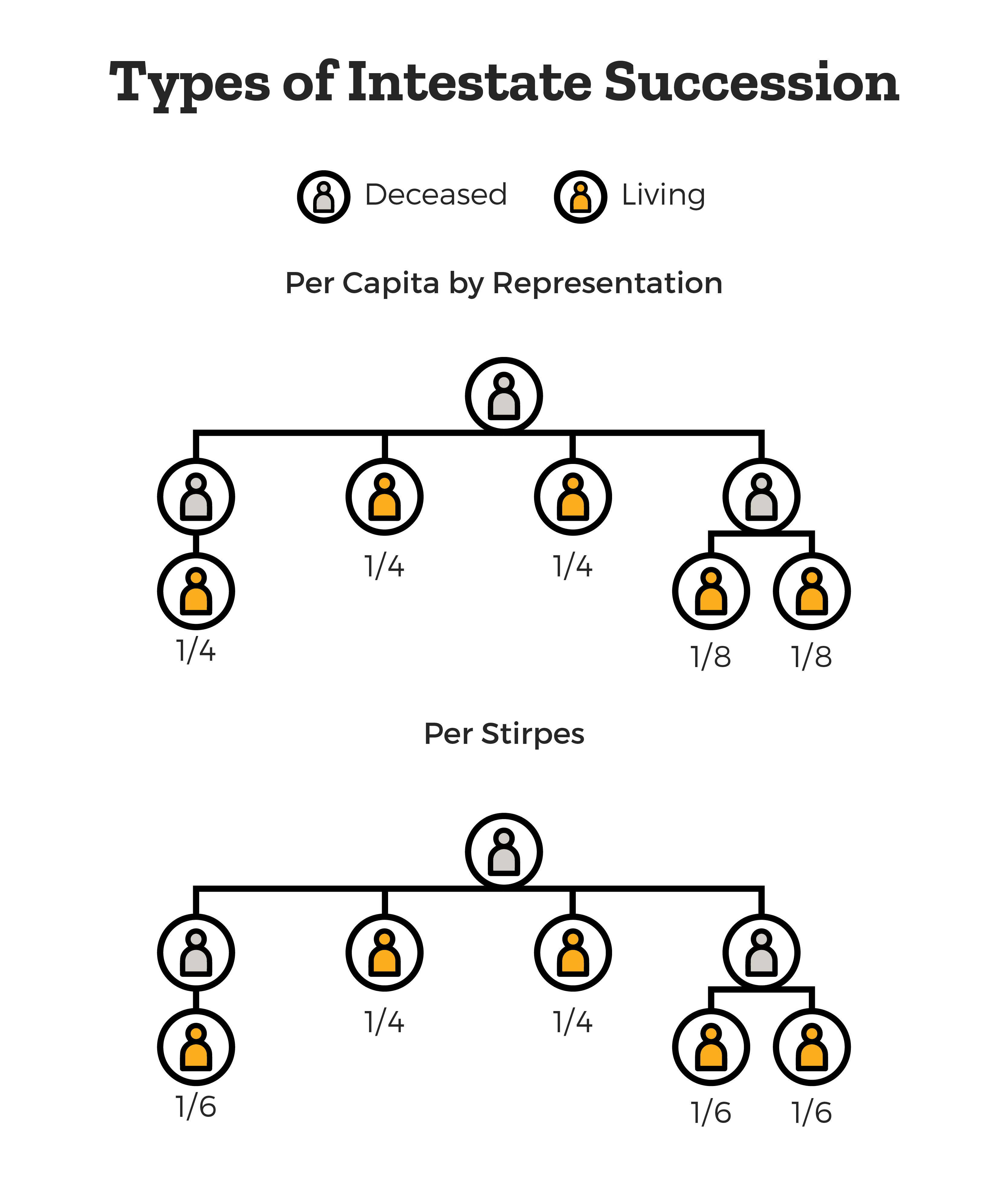

In most states, the remaining balance of an estate is distributed by “per capita by representation.” In other states, the “per stirpes” model of distribution is used.

What is per capita by representation?

In a “per capita by representation” state, the remaining property is divided equally among the first generation of living descendants (usually the decedent’s children). If a member of the first generation has predeceased the testator, then the share of the predeceased person will pass to his or her direct descendants “by representation.”

What is per per stirpes?

In a minority “per stirpes” jurisdiction, such as in Florida, equal shares are distributed to each of the decedent’s children. Any remaining shares are then distributed evenly among subsequent generations.

Who Can Be a Witness to a Will?

A witness to a will must be a competent person of the age of majority.

Can an “Interested Person” Be a Witness?

An “interested person” to a will is anyone who could potentially inherit. The fact that a will beneficiary can be a witness does not affect the validity of the will; however, the bequest to the interested witness is void, UNLESS:

- There were at least three witnesses and two were disinterested (therefore, the signature of the beneficiary-witness is not needed to admit the entire will to probate; or

- “Whichever is least rule”; The interested witness would have been an intestate beneficiary (without a will), in which case the witness-beneficiary takes the lesser of the will inheritance or the intestate share as defined by state statutes.

What Is A Self-Proving Affidavit?

A self-proving affidavit is a clause appearing before a witness’s signature that states that all the elements of due execution were fulfilled and sworn in front of a notary public. This means that at the time of the probate court, a witness would not need to be produced to execute the will.

Can You Contest A Will?

Someone may contest a will and attempt to invalidate it due to factors such as forgery, fraud, or lack of capacity.

If someone wishes to challenge a will, an interested party must file with the court within six months of the will being admitted probating.

What is an interested party in a contest?

An interested party in a contest is a person who would be adversely affected if that will were probated. The interested party filing a contest must show proof that the will should be made void.

In most will contests, an interested party wishes to void a last will and testament due to the testator’s lack of capacity or sound mind at the making of the will.

A person challenging a will based on lack of capacity has the burden of showing that the person was incompetent at the will signing, based on insane delusion, fraud, or undue influence.

How can insane delusion void a will?

A will may be void due to “insane delusion” when the testator had an unreasonable belief of their property, which any normal person would know is not true. An insane delusion points to evidence that the testator was not of sound mind and could not distribute property they were mistaken about.

Can a will be deemed invalid?

A will is deemed invalid due to fraud when the testator was intentionally deceived while making his or her estate plan. Fraud may occur in several ways, from the testator not having the full information of the value of his or her entire estate to the deception of any other material fact represented in the will.

How does undue influence void a will?

A will is deemed invalid due to undue influence in situations where influence was exerted, the influence overpowered the free will of the testator, and the resulting will would not have been executed but for the influence. Generally, undue influence occurs in situations where a close friend or family member took advantage of the testator.

What is a Holographic Will?

A holographic will is a type of will that is completely written in the testator’s handwriting and signed by the testator but has no witnesses. Most states will allow for the probate of holographic wills.

Some states, like New York, however, do not allow holographic wills save for emergency situations, e.g., armed forces during war and mariners stranded at sea.

How Do You Revoke A Will?

A person can revoke a will by:

- Physical act such as burning, tearing, cutting, canceling, obliterating, or other act of mutilation

- Subsequent testamentary instrument, such as a new will or codicil (supplement), stating that the original will is no longer valid. There should be implied revocation language, such as “I hereby revoke all wills heretofore made by me.” If there is no such language, the two documents are considered together. The first being considered the primary, and the second being treated as a supplement that only revokes the first will to the extent that there are inconsistencies.

What Are Codicils and How Do They Change A Will?

A codicil adds or supplements a will and effectively republishes the original will as of the new date. The execution of a codicil may affect advancements, the rights of after-born children, and a possibly divorced surviving spouse.

A properly executed codicil may also revive an earlier will that was expressly or impliedly revoked by a subsequent will. In this case, the testator will have to instruct that he or she wants to revive his or her original will.

What Happens If A Will Is Lost?

If a testator’s last will was last known to be in his or her possession, yet the will cannot be found after his or her death, there is a “very strong presumption” that the testator destroyed it, unless its existence can be explained by clear and convincing evidence.

How Does A Divorce or Annulment Change A Will

In most states, if a divorce, annulment, or separation judgment decree is granted after the creation of a will, it automatically revokes a bequest in a will to the former spouse and any provision naming him or her executor or trustee. The will is read as if the former spouse has died, and the division of assets will continue to the next people in succession.

However, probate laws that eliminate the former spouse as a beneficiary do not apply to life insurance policies.

If one gets married after the execution of a will, the marriage will not have any effect on the prior will. In some states, however, the new spouse can take an intestate share under the “omitted spouse” doctrine, which will make a provision for a left-out spouse unless the new spouse was intentionally omitted from the will or the will was made during the contemplation of the new marriage.

If you have gone through a major life change, such as a divorce, marriage, or new children, it is important to revisit your estate planning documents, as you may need to make a new will to ensure that property will be left to your family members as you see fit.

Who Cannot Inherit?

In general, people are free to choose their own beneficiaries and can freely choose to disinherit any family member. A few laws, however, prevent some people from inheriting in certain situations.

Failure to Survive by 120 Hours

When the transfer of property depends on a beneficiary surviving the testator (deceased), the beneficiary must survive the decedent by 120 hours (five days). Otherwise, the testator’s property, any relevant life insurance payments, and intestate distribution pass as if the beneficiary predeceased the testator.

Renunciation

In some cases, a spouse or other interested party may make a legal contract, such as in a prenuptial agreement, that they renounce any potential inheritance.

Slayers Can’t Inherit

The “slayer rule” states that a beneficiary who intentionally kills the testator cannot inherit under the will. The slayer is likewise precluded from sharing in the intestate estate, a life insurance policy, or testamentary trust.

Pretermitted Child

Most states have laws for “pretermitted children,” which concern minor children who have been born or adopted by the testator after the will. In these cases, the court looks at whether the child was intentionally left out of the will and whether the testator would have intended to include this child if he or she had known. If it is found that the testator would not have purposely disinherited the child, then the child will take an intestate share.

What Are Lapsed Gifts?

When a potential beneficiary dies during the testator’s lifetime, any predetermined gifts will “fail” or “lapse” unless the gift is saved by the state’s anti-lapse statute.

An anti-lapse statute will direct a gift be given to the descendants of the predeceased beneficiary. However, an anti-lapse statute can be defeated by specific language in a will, such as, “… to my brother Ben, unless he dies before me, then to my cousin Joe.”

What Is an Advancement of a Will?

An “advancement” of a will is when a beneficiary of a will receives all or part of his or her expected inheritance during the lifetime of the testator (before the will comes into effect). For a valid advancement, there must be contemporaneous writing signed by both the beneficiary and the testator, with the intention that the gift is treated as an advancement.

What is a Living Will?

A living will is a separate legal document from a last will and testament. A living will states a person’s wishes regarding any future medical treatment or health care decision.