What is a will? An overview of last will and testament in New York.

A will, or last will and testament, is a legal document that is intended to convey how to distribute one’s property after their death. The term “property” in the context of the legal document refers to real estate property, personal property, and money.

New York laws regarding wills are codified under the New York Consolidated Laws, Estates, Powers and Trusts Law, also known as NY EPT Law.

A will is a major part of estate planning, as it is a legal document detailing one’s final wishes for how they want to distribute their property.

Usually, people want their belongings to go to their descendants (the people next in line in the family); however, a last will and testament can make directions for gifts to certain loved ones. A will can also give specific instructions for funeral arrangements and care of one’s minor children and pets after his or her death.

As your last will and testament is a serious and complex legal document that involves major reflection, it is highly advised to consult a New York estate planning attorney prior to drafting a will.

Who can make a will? What is a sound mind?

A person who writes a will is called a “testator.” A person named in a will to receive property or a gift is called a “beneficiary,” or an “heir.”

New York Consolidated Laws, Estates, Powers and Trusts Law provides that, “Every person eighteen years of age or over, of a sound mind and memory, may by will dispose of real and personal property and exercise a power to appoint such property.” Thus, any adult over the age of 18 can make a will if they have a “sound mind.”

What is a sound mind? It means that the testator understood their property and had the intent to make a will. A person without a sound mind would be a person who is experiencing mental illness, is under the influence of drugs, or is otherwise unable to think rationally enough to write a will.

A person who is experiencing “undue influence” also cannot make a valid will. Undue influence occurs when a person is controlled by another. It is similar to being forced; however, the person controlling is usually a close family member trying to persuade the testator in their favor. The presence of undue influence will invalidate a will. Similarly, a will made by a person under duress, or by the threat of force, will also be found invalid.

How to make a valid will in New York: 7 requirements

There is a (seven-part) test detailing the legal requirements that must be followed to write a valid will in New York.

- Must be 18 years of age to have capacity

- Signed by the testator, or by someone at the testator’s direction and in his or her presence, i.e., “by proxy.” If there is a proxy signing for the testator, such proxy must also:

- Sign their name as the proxy

- The proxy cannot be counted as one of the two needed attesting witnesses; and

- The proxy shall affix his or her address (but failure to affix address does not invalidate the will)

- The testator’s signature must be “at the end, thereof.” Anything written in the will after a signature is given no legal merit.

- The testator must sign the will or acknowledge his or her earlier signature in the presence of each witness.

- The testator must “publish” the will, meaning that he or she communicates to the witnesses that this is, in fact, his or her last will and testament.

- The will must be signed by at least two attesting witnesses.

- The execution ceremony must be completed within a 30–day period. The 30-day period begins when the first witness signs.

A self-proving affidavit

A self-proving affidavit is not a required component of wills in New York; however, it is often incorporated. A self-proving affidavit is when the witnesses sign a sworn statement in the presence of an attorney that recites that the will is correct (satisfies the seven-part test.) A self-proving affidavit can substitute for live testimony and is particularly useful when a witness cannot remember, or when the witness later becomes hostile and doesn’t want to remember.

Will interpretation – What happens if there is a confusing or ambiguous phrase in the will?

Interpretation is the main concern for determining the intent of a New York will. New York law looks at what the actual intent was by looking at the document’s “plain meaning.” Sometimes, however, there is no “plain meaning” in a will due to conflicting meanings or confusion. As such, extrinsic evidence may be allowed to determine a will’s meaning where there is “latent ambiguity.” New York law allows extrinsic evidence, such as details of the facts and circumstances surrounding the creation of the will, and any evidence by third parties.

If the extrinsic evidence still does not cure the ambiguity, that specific portion “fails” because there is no clear beneficiary or clear meaning of the document.

Changes to a will

Under New York law, there are only two ways a testator can make changes in their will:

- Write a new will that revokes the first will; or

- Make a codicil, which is an amendment to the first will, changing only parts of the first will. It is simply a supplement to the original will.

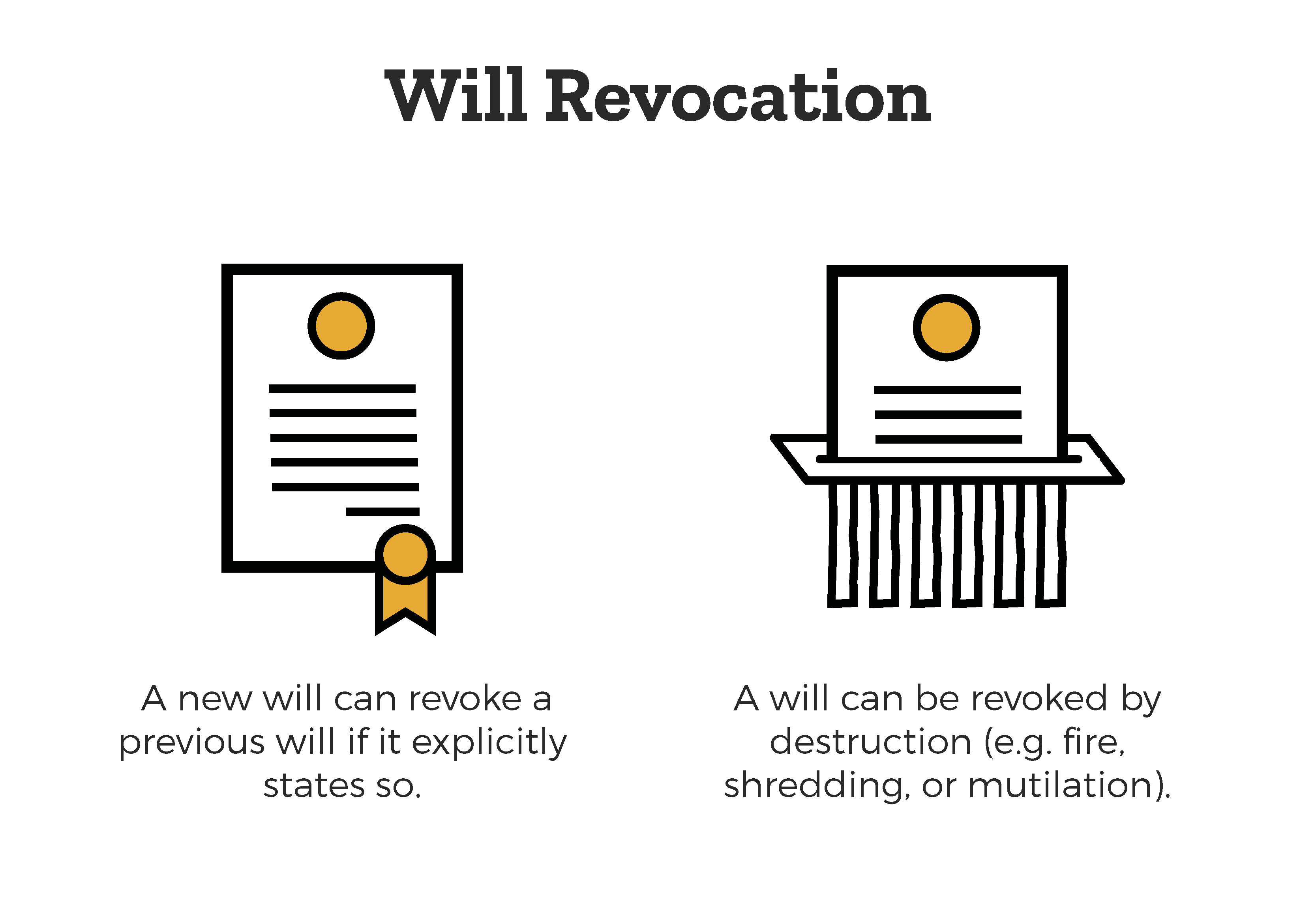

Revocation

One can revoke (cancel) or change a will in New York up until the testator dies. However, proper procedures must be taken so as to prevent future confusion.

Under New York law, a will can be revoked by destruction (e.g., complete destruction, fire, cutting, or mutilation). A new subsequent will can also revoke a previous will if the new will states so. All acts must be done by the testator with the intent of revoking the original will.

Codicil

A codicil is an amendment or addition to a last will and testament. It does NOT make your original will invalid; it simply supplements it. The rules for making a codicil in New York follow the same legal requirements for a standard will, including requiring the signature of two disinterested witnesses.

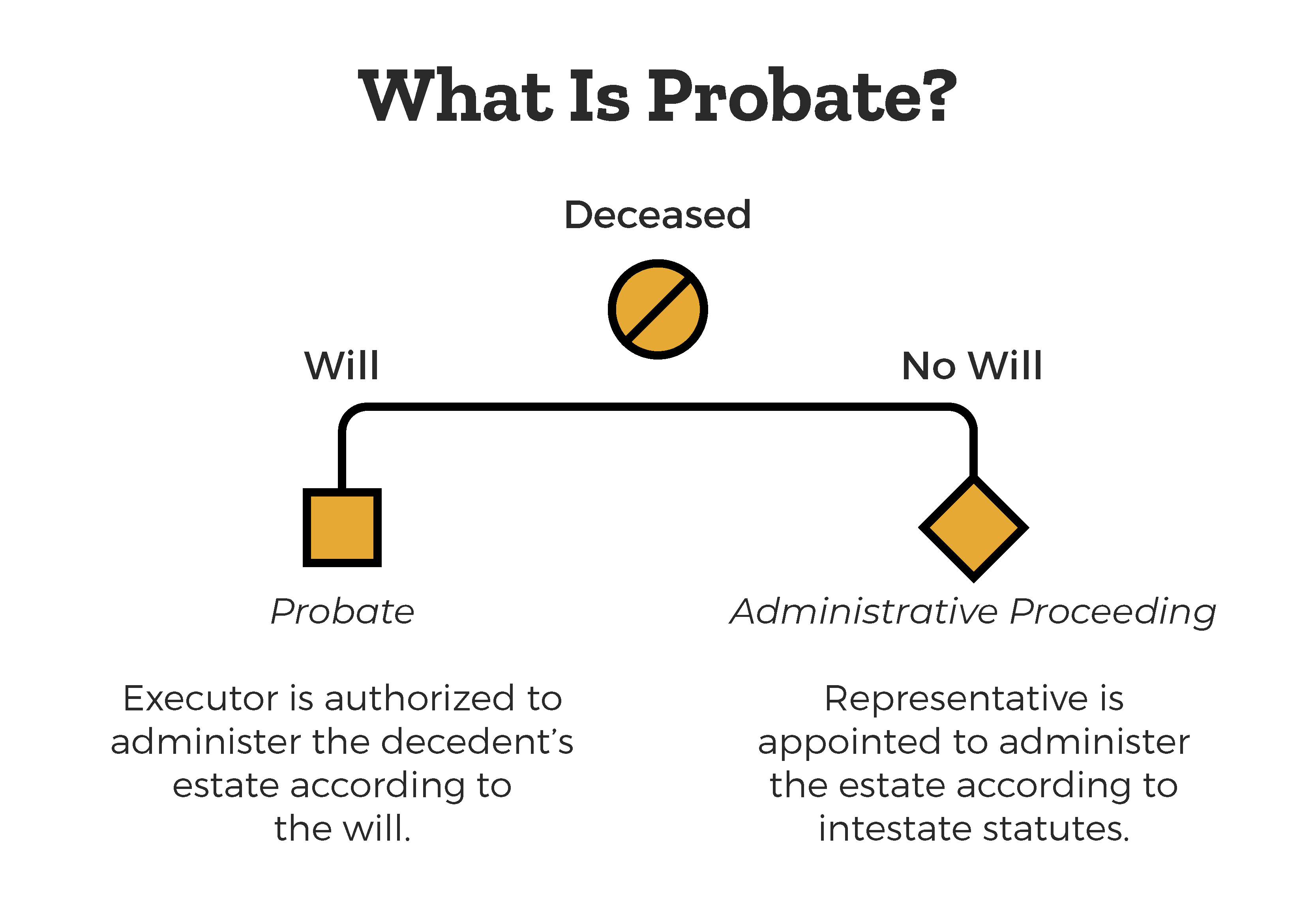

Probate – What is probate? How can you avoid it?

A will in New York must be admitted to probate in a New York surrogate’s court. Probate is a legal proceeding to administer the property of a person who dies with a will. Probate is a process necessary to validate a will. The executor named in the will must go to court and prove that the will is real and valid. The executor can’t distribute the estate to the heirs until after the will goes through probate. First, however, all New York estate taxes, as well as all outstanding debts, must be paid. The “residuary estate,” that is the balance of the testator’s estate after all claims, estate taxes, and “particular” bequests have been distributed, is considered the “rest” of the estate to be given to the heirs.

The time and costs of going to probate can be a nuisance; however, it is necessary to legally enforce a will. Without the requirement of proving the will in court, anyone may be able to produce a forged will claiming inheritances.

Can one avoid probate?

If one dies without a will, there is no need for a probate proceeding. However, sometimes, probate can be avoided even with a will.

Generally, small estates consisting of $30,000 or less can be settled without going to a surrogate’s court. The surviving spouse would first have to produce the certificate of death and bring it to the financial institution or insurance company to collect.

Intestate – What happens if you die without a will?

To die without a will is called to die “intestate.” The New York law on intestacy aims to distribute the decedent’s estate in a way that most likely would have occurred if the person died with a will (e.g., to a surviving spouse and minor children first).

As there is no will to be probated, the court will instead hold an administration proceeding at which a representative, or an “administrator,” is appointed to handle the estate. The administrator is responsible for finding the heirs who will inherit property under the New York intestate succession law.

The New York intestacy law of distribution is as follows:

- Intestate Decedent Survived by Spouse But No Children

- Surviving spouse takes the whole estate

- Intestate Decedent Survived by Spouse and Children

- Surviving spouse takes the first $50,000 and half the residuary estate

- The balance of the estate is then divided equally

- If the estate is less than $50,000, the whole estate goes to the spouse

- For New York intestacy law, nonmarital children and adopted children are treated the same as marital and biological children and will inherit as such.

- Intestate Decedent Survived by Children ONLY

- If all children are alive, they receive the entire estate in equal shares

- Intestate Decedent Survived by Children and Issue of Predeceased Children

- The estate passes to alive children or issue of the predeceased children “by representation,” called “per capita at each generation.”

Three Steps to Determine Intestate Shares

- Divide the estate for each of the heirs at the first generational level at which there are survivors

- All living people at that first generational level take one share each.

- The shares of the deceased persons at the first generation level are combined and then divided equally between the people at the next generation in the same way.

Result: All persons in the same generation are always going to have equal shares of the estate.

- Intestate Decedent NOT Survived by Spouse or Issue

- Passes all to parents or surviving parent

- If Not Survived by Parents

- Passes to issue of parents (brothers, sisters, issue of deceased brothers and sisters) who take per capita at each generation

- If there are no longer any parents or siblings alive, the estate “escheats,” or goes to the state.

Bars to succession – When can a person NOT inherit?

- Slayers – The “slayer rule” states that anyone responsible for the death of the decedent cannot stand to inherit in their estates. For example, Lyle and Erik Menendez are brothers whose parents were found murdered. Erik and Lyle were the only issues of the parents and, as such, stood to get the entire estate. Later, Erik and Lyle were found guilty of murdering their parents. Even though Lyle and Erik were potential heirs, they are now disqualified, as they were responsible for their parents’ deaths.

- Spousal disqualification: A spouse may be disqualified from taking their share by “disqualification,” either by divorce, legal separation, abandonment, or invalid “void” marriage.

- Failure to survive by 120 hours: An heir must survive the testator by 120 hours, or a five-day period. If not, the heir’s death is considered contemporaneous as the decedent, and they will be treated as if they had predeceased the person.

- Renunciation: The potential heir decides they don’t want the gift, and they renounce it. The person who disclaims is considered to have predeceased the testator.

- Advancement: An “advancement” occurs when a potential heir collects their inheritance during the life of the donor. As such, there must be some evidence that the advancement was intended as an “inheritance in advance” and not just a gift. Qualifications for advancement are: contemporaneous writing signed by the donor and donee, with the evidencing intention that the “gift” be treated as an advancement.

Trusts

What is a trust? A trust is when one person, the “trustee,” is appointed to hold a property interest, subject to an obligation to keep or use that interest for the benefit of another person. A trust is a commonly used document in estate planning, yet not as common as a will.

A living trust, also legally referred to as an “inter-vivos trust,” is a trust that is created with the purpose of distribution during one’s life. Once a living trust is signed, it becomes immediately effective. Additionally, a living trust is irrevocable; that is, it cannot be changed once it has been put in motion.

A living trust is also not the same as a “living will,” which is neither a will nor a trust but a document detailing one’s end-of-life health care and medical wishes.

A trust that is created and incorporated in a will is called a testamentary trust. Different from a living trust, a testamentary trust will not become effective until after the testator has died and the will is admitted to probate. This is because a testamentary trust, just like a will, can be changed or revoked up until the time of the person’s death.

Living wills

A living will is not a will or trust but a document detailing medical and health care wishes. Living wills usually appoint a “power of attorney” who is in charge of making decisions and/or carrying out the specific instructions in the document. Many living wills today also contain a person’s choice of whether to continue life support treatment if they were to be incapacitated.