Guide to Ownership and Estates

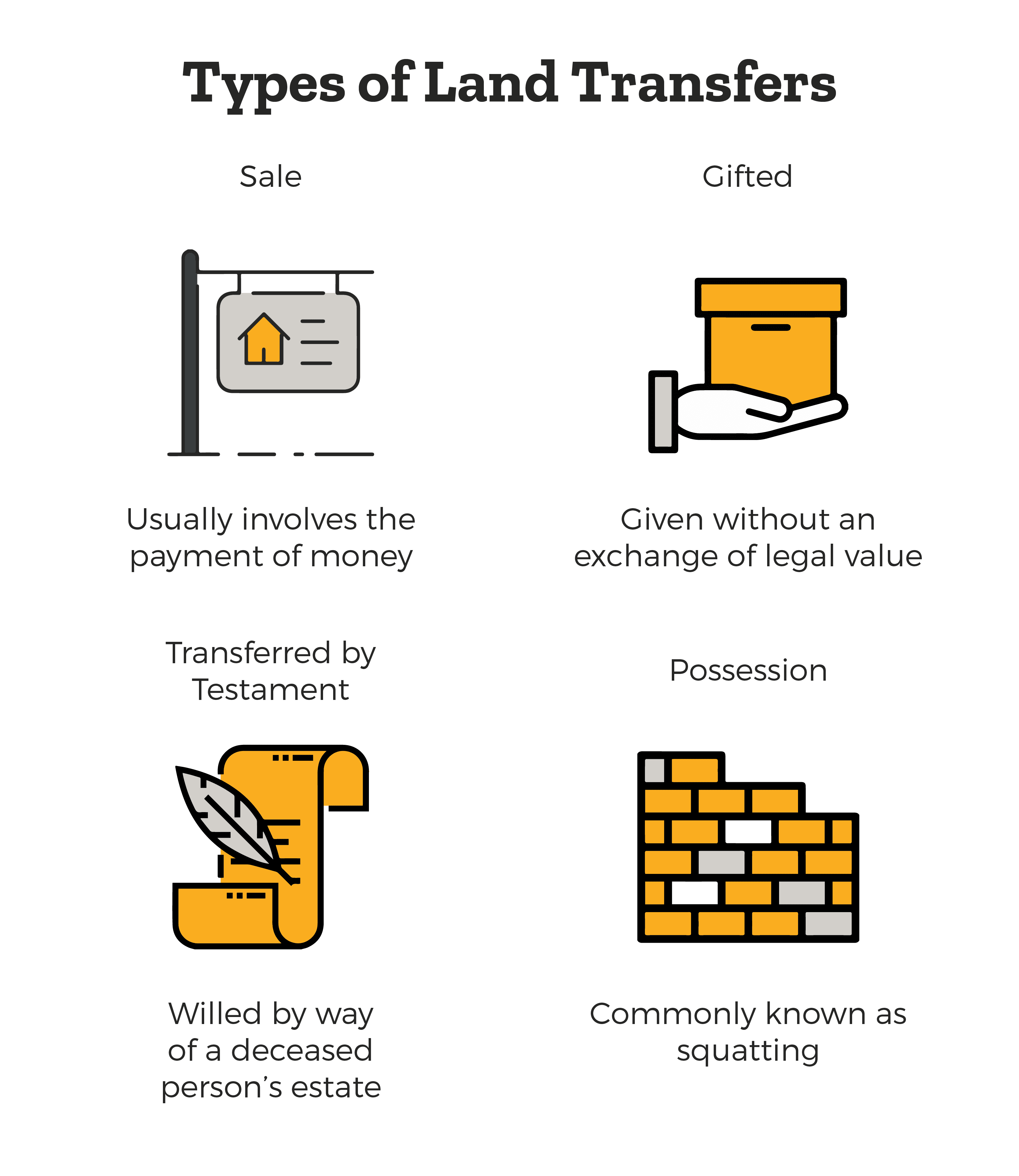

American real estate law provides four main ways by which ownership of land (in the legal context, the land is often referred to as real property) may be transferred between successive owners. The first, and perhaps the most common, is by sale. This type of transfer usually involves the payment of money (or something that has legal value) from one owner to another. Land may also be gifted to a new owner (without an exchange of legal value). For estate planning purposes, landownership may also be transferred by testament (most commonly known as a will) by way of a deceased person’s estate.

If the owner dies without specifying a successive owner in a will, the state will seek to pass ownership of the land to a member of the deceased landowner’s family as dictated by state statute. This type of transfer is known as intestate succession. Finally, landownership may be acquired by possession (commonly known as squatting). This method is typically the least common because states are reluctant to give land to unauthorized possessors (adverse possession). Thus, to prevent fraud, states have imposed strict criteria in such situations that make this form of transfer more difficult to complete.

As dictated by property law, landownership also takes several forms, which serve different purposes according to the intent of the transferor landowner. These forms in the legal context are referred to as estates. An estate that provides the successive owner with a perpetual (capable of lasting indefinitely) and unrestricted estate is the fee simple. However, the fee simple may be modified to include some restrictions that may limit its duration and/or usage terms, provided the parties establish such terms by agreement. A more limited form of the estate that only lasts the duration of the occupying person’s life is known as the life estate. For example, an owner may allow a nonfamilial friend to have absolute possession and control of a property until the friend dies. Upon the friend’s death, possession and control of the property will revert to the original owner.

Land Sales and Purchases

As noted earlier, landownership may be transferred by sale. Each state has a variation of what is known as a statute of frauds, which is intended to prevent fraud in many of these transactions. This type of statute requires that all transactions involving land be memorialized in writing that meets certain types of criteria, such as the names of the parties in the transaction, price, and a legally adequate description of the property being sold. Upon completion of such writing, the sale has reached what is known as the contractual stage. This stage of the process is somewhat complex because the parties have expressed intent to complete a legal exchange, but the sale has not been completed until a deed has been formally completed to make the transfer effective.

To resolve some of this complexity, the law has conceived what is known as the doctrine of equitable conversion. This doctrine dictates that during the contractual stage of the transaction, the buyer bears the risk of the loss. For example, if the parties form a sales contract, and a hurricane destroys the house before the deed is executed, the buyer is responsible for the cost of rebuilding the house unless the parties agree otherwise. However, the seller is obligated by law to provide the buyer with a marketable title. A marketable title means that the title to the property is free from encumbrances such as liens or third-party ownership claims (capable of being legally transferred). The seller must also disclose all known defects relating to the property.

Upon completion of the contractual stage, a formal procedure will be conducted to complete the sale. This procedure is known as the closing. The primary purpose of this procedure will be to execute and transfer the deed to formally complete the sale, although many other outstanding real estate-related issues are often resolved at this time. Many people prefer to have a real estate attorney present during this time to ensure that the closing process is completed legally and smoothly. While the primary role of the real estate agent is to locate a qualified buyer in exchange for a commission, the agent may also be present at the closing to assist.

Once the sale is completed, the contract will merge into the deed, and the terms of the deed will supersede the contract. Several types of deeds may be employed to complete the transfer, and they are mostly based on the extent to which the seller provides warranties to the buyer. A seller may also include an “as-is” clause in the sale, which disclaims the seller’s liability relating to unknown defects at the time of sale. If either party fails to complete their end of the deal, there are various remedies available to buyers and sellers. Most notably, the land is considered unique for legal purposes. This means that no two pieces of property are exactly alike, including identical apartments situated in the same building. The law provides that a court may order a seller to complete a sale if a financial award (damages) is not sufficient.

Recording Statutes

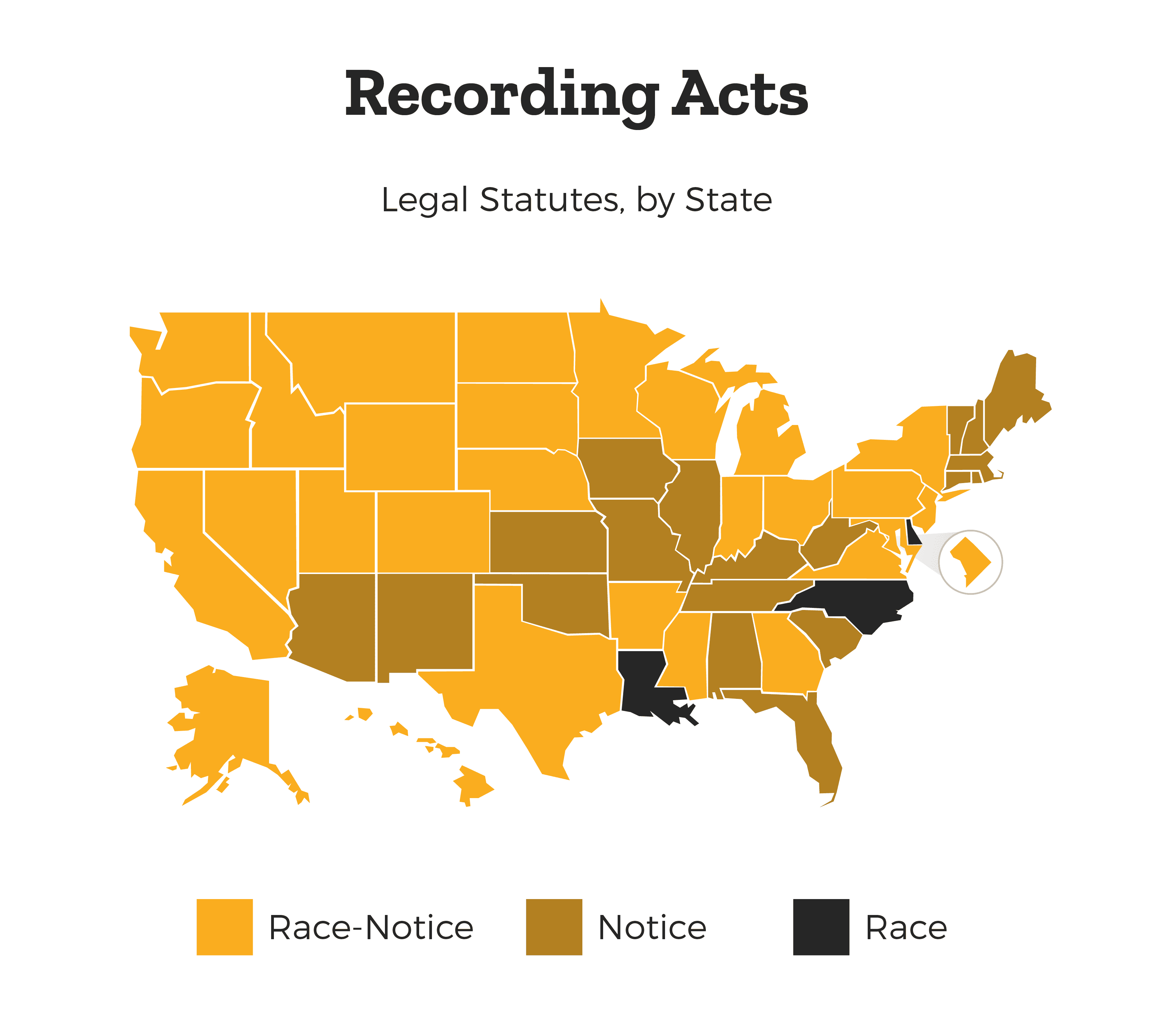

Once the sale is completed, it must be recorded within local government records. The purpose of recording is to notify officially other prospective owners that another owns the property. Predictably, there are often discrepancies that occur in the transfer process. Thus, different states have established rules by which new landowners establish claims to the title. A race state (as the name implies) will give priority to any rightful owner who records their deed first. A notice state will provide a title to any subsequent purchaser who has purchased the property without knowledge of a prior unrecorded claim by another buyer (legally known as a bona fide purchaser). Finally, a race-notice state will give the good title only to the purchaser who wins the race to record and purchase the property without notice of prior title claims.

Security Interests in Land

Sellers often seek financing to purchase land. In turn, lenders often provide financing based on what is known as a security interest in the land being transferred. The most common form of such an interest is a mortgage. Mortgages are based on the concept that a lender will provide financing to a buyer to purchase property, and the buyer must repay the loan in monthly installments, plus a reasonable rate of interest (often limited by law). If the buyer can no longer make the installment payments, the lender has the right to take possession of and sell the property. This process is known as foreclosure. Before this process is completed, the buyer is afforded a right of redemption. This means that a buyer may cure the delinquency and avoid the foreclosure process through various forms of remediation, such as paying the unpaid mortgage installments. Some other examples of security interests in real estate property include: deeds of trust, installment land contracts, and absolute deeds.

Land Use Restrictions

Many situations arise between landowners that prompt someone to use or prohibit the use of someone else’s property for specific purposes (public or private). For example, if a property owner wishes to preserve the view of a nearby beach. She may create an agreement with neighbors to limit the height of all new buildings built on neighboring properties. This is what is known as a covenant because it touches and concerns the land (directly affects the physical nature of the property), and it runs with the land (affects the land on an ongoing basis). If a portion of the land is to be used or restricted, a landowner may provide what is known as an easement. For example, if the only way by which a landowner may gain access to his or her property is by crossing someone else’s property, an easement may be granted in such situations granting access to the landlocked owner. An easement may be created and terminated in various ways, whether formal and informal.

Rental of Real Estate: Landlord-Tenant

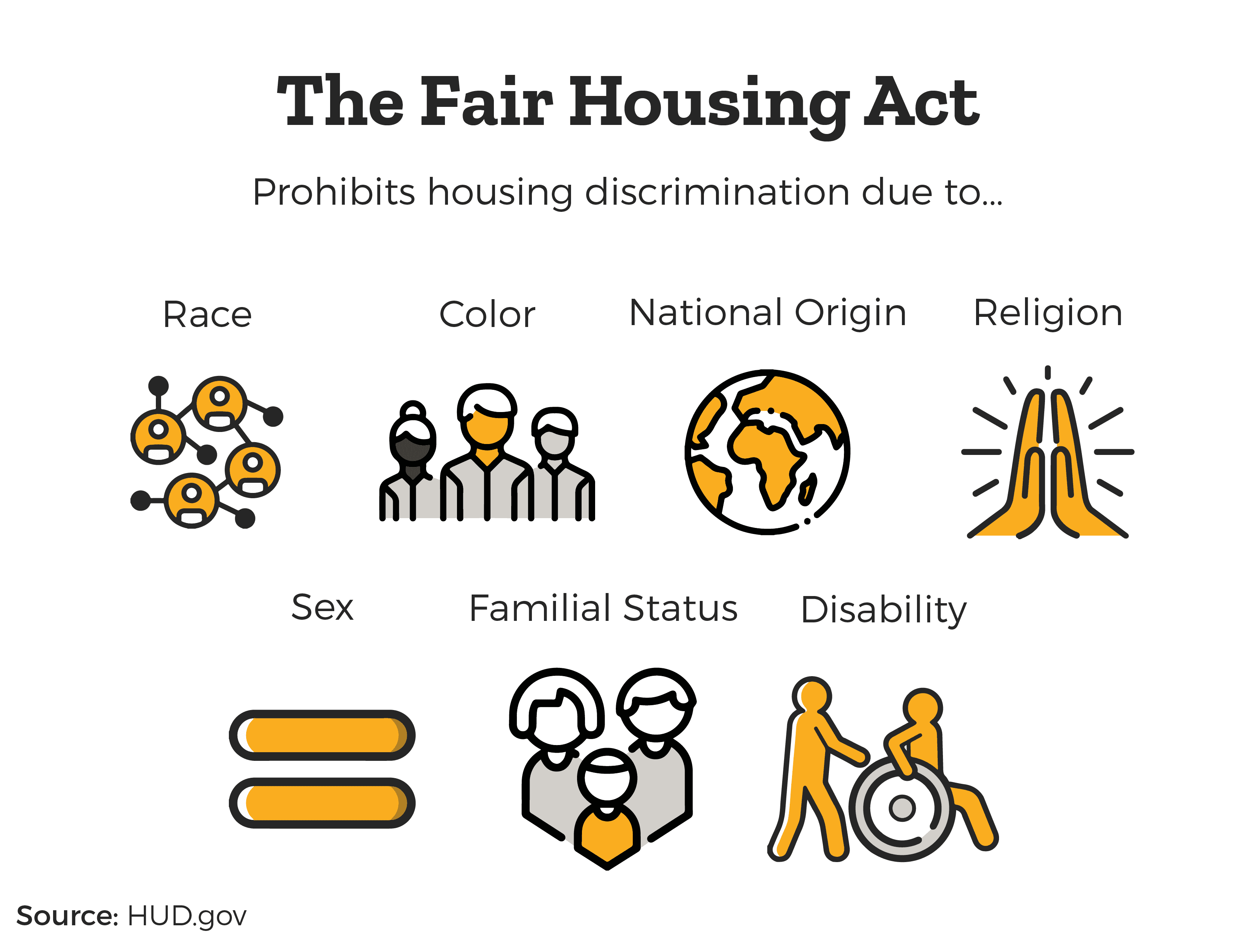

Each state has laws that govern rentals of real property. Generally, landlords are required to provide property, subject to certain warranties. Most notably, the implied warranty of habitability requires the landlord to provide a tenant with property in a condition in which people can safely live. This may include such features as hot, running water. Another warranty that landlords are required to make to their tenants is the covenant of quiet enjoyment. This warranty guarantees that landlords will not invade or interfere with a tenant’s use of the property. For example, a landlord may not enter the interior of an apartment without the tenant’s permission. Landlords are also required to make repairs in all cases involving residential property but not in commercial real estate. The Fair Housing Act (federal law) also mandates that landlords may not discriminate against potential tenants based on race, religion, gender, or age.

Generally, the tenant’s (and subtenant’s, if any) primary warranty is to pay rent. However, the tenant is also required to avoid committing waste. This broadly means that a tenant must take reasonable care of the property by reporting defects to the landlord and avoiding the destruction of the property. Notably, if a tenant makes improvements to a property without the landlord’s consent, this also may be considered waste. The nature of the rental agreement may also take many forms. These agreements range from long-term, formal agreements such as leases to short-term, informal agreements such as a tenancy at will (either party may terminate the arrangement at any time).